Child labor existed prior to capitalist societies. In fact, having children was one of the main ways a family would get the labor for their farm.

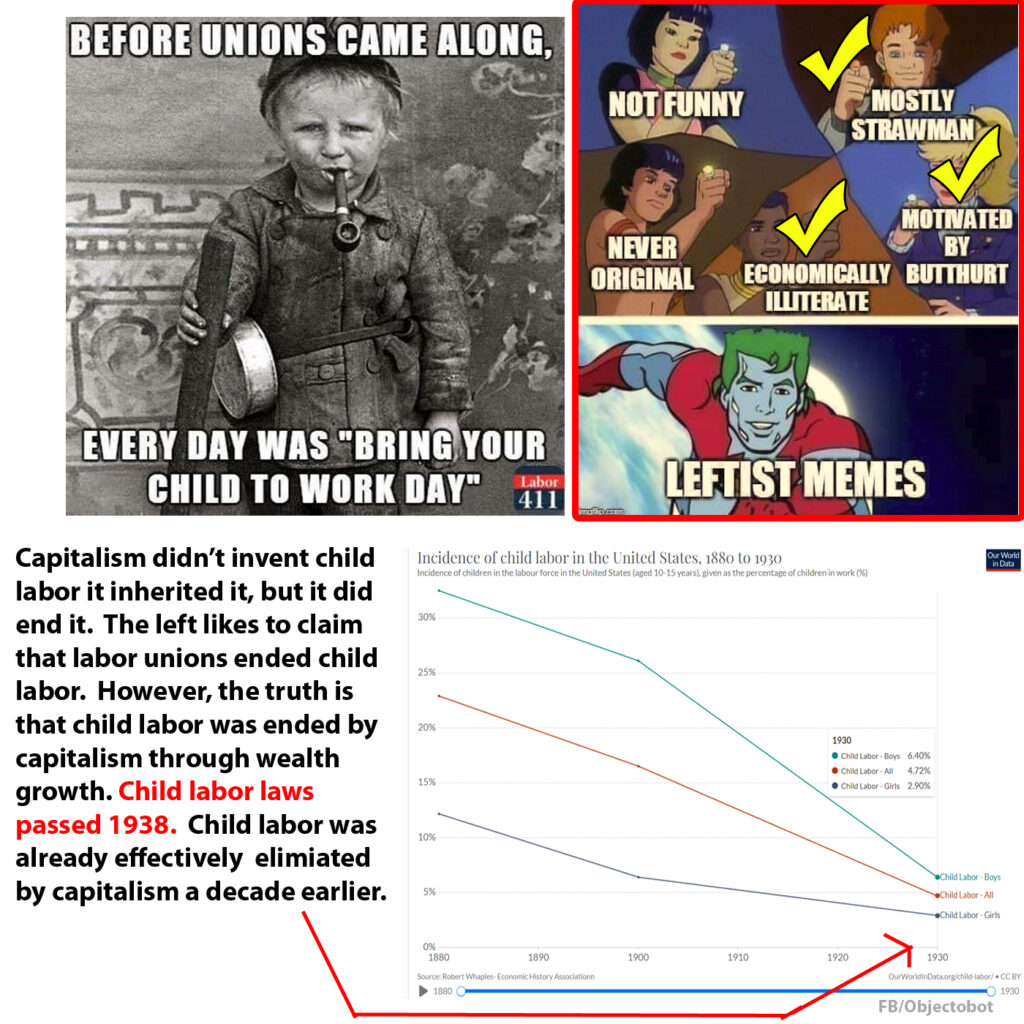

When I posted the above image showing that child labor was virtually eliminated a decade before any labor laws were passed in 1938, thus debunking the narrative that child labor was ended by Unions, I received a lot of objections.

This post will be dedicated to addressing those objections.

This first objection asks the question of why am I focusing on laws. After all, unions advocated for less child labor without passing laws, and there was even a national child labor committee established in 1904 to also advocated for ending child labor. I don’t want to say that unions and committees had absolutely no impact, but 1904 is not a special date as child labor rates were already declining. This objection also ignores the fact that mothers were keeping their children out of dangerous workplaces long before labor unions were codified. Parents didn’t send their children to work because they wanted to and had to be told not to, they sent them to work out of necessity. The question is what ended that necessity. My position here that capitalism slowly ended this necessity is not anything out of the ordinary. “Most economic historians conclude that it wasn’t laws or labor unions that ended child labor but that industrialization and economic growth brought rising incomes, which allowed parents the luxury of keeping their children out of the workforce.” -Robert Whaples, Wake Forest University.

Once that line of reasoning fails the objections try to bring it back to laws. Saying that there was a federal child labor law passed earlier in 1916, or that states were passing their own child labor laws the entire time. The 1916 law only lasted 2 years and was overturned in 1918, and besides, by 1916 the child labor rates already plummeted. What about the child labor laws passed by the states? Well that is something that is a matter of study. Moehling (1999) finds that the employment rate of 13-year olds around the beginning of the twentieth century did decline in states that enacted age minimums of 14, but so did the rates for 13-year olds not covered by the restrictions. Overall she finds that state laws are linked to only a small fraction – if any – of the decline in child labor. It may be that states experiencing declines were, therefore, more likely to pass legislation, which was largely symbolic.

The next line of reasoning states that if it wasn’t the state child labor laws, then it must have been the state compulsory schooling laws that took children out of the workforce and into schools. However, this argument also has a huge problem. 2012 paper “DO SCHOOLING LAWS MATTER? EVIDENCE FROM THE INTRODUCTION OF COMPULSORY ATTENDANCE LAWS IN THE UNITED STATES, ” explains that compulsory attendance laws minimum term lengths were short, schooling laws were not always

enforced, and or had exceptions for employment. Thus, children – even young children – could easily be working full time or close to full time for most or all of the year.

Do I think that capitalism deserves 100% of the credit for ending child labor? Probably not 100%, labor unions most likely did have an impact, but capitalism certainly deserves most of the credit and historians agree. Unions did pressure legislatures to restrict the employment of children, but it was the falling demand for child labor driven by improving conditions that also reduced opposition to child labor legislation, allowing activists to push their reform in a largely symbolic manner.